Caucasian Albanian language

Jost Gippert (University of Hamburg)

In the course of the Christianisation of the Southern Caucasus in the 4th–5th centuries of our era, a third language of the region, along with Armenian and Georgian, was equipped with an alphabet to be used for writing down biblical texts. The language is usually named “Albanian” in accordance with Greek sources that denote the region in question, north-east of antique Armenia, as Ἀλβανία and its inhabitants as ἄλβανοι, a designation that is also concealed in the Armenian name, Aghuankʽ [Bais 2001 and 2023; Dum-Tragut/Gippert 2023]; there is no relation with the (Indo-European) Albanian language of the Balkans. Even though the existence of the Albanian script and Christian texts written in it had been a topos since Antiquity, esp. in the historical accounts of Koryun and other Armenian authors, it took until 1832 for the first elements of the Albanian language to be identified in a list of month names written in Armenian characters in an Armenian manuscript of Paris (BNF, arménien 252, 43v)[Brosset 1832; Gippert et al. 2008, II-94-95; Gippert 2023, 221-225], and the first specimen of written Albanian came to light only in 1937 when an alphabet list of the Aghuankʽ was detected in a 13th-century Armenian manuscript of the Matenadaran in Yerevan (M 7337, 145rv) (see Albanian script). A few years later, in 1948, some inscriptions whose letters bore enough similarities with the alphabet list to be regarded as Albanian were unearthed near the Kura reservoir in Mingachevir [Qaziyev 1948, 399-401; Vahidov/Fomenko 1951, 97-98; Gippert 2023, 97-99]; however, no reliable reading was possible until the 1990s when the remnants of Albanian manuscripts were detected in the lower layer of two Georgian palimpsest codices of St Catherine’s Monastery on Mt Sinai [Aleksidze/Mahé 1997; Gippert et al. 2008; Gippert 2023, 99-141]. With the decipherment of the Albanian palimpsests, which turned out to contain biblical matter, comprising about half of the Gospel of John from an evangeliary and pericopes from the other Gospels as well as the Acts of Apostles, the Pauline and Catholic Epistles, and the prophet Isaiah together with Psalm verses, the structure and the lexicon of the Albanian language have meanwhile been established with certainty [Gippert et al. 2008, II-1-84 and IV-1-71; Gippert/Schulze 2023]. It is clear now that the Albanian language was a member of the (North-)East Caucasian family, more exactly its Lezgic branch, with the modern Udi language being its closest relative (if not its direct descendant) [Gippert et al. 2008, II-65-78; Schulze/Gippert 2023]. This is proven not only by a great bulk of common items from the basic lexicon (especially verbs) but also by straightforward matches in the grammatical structure that can be regarded as decisive (for details see Udi language).

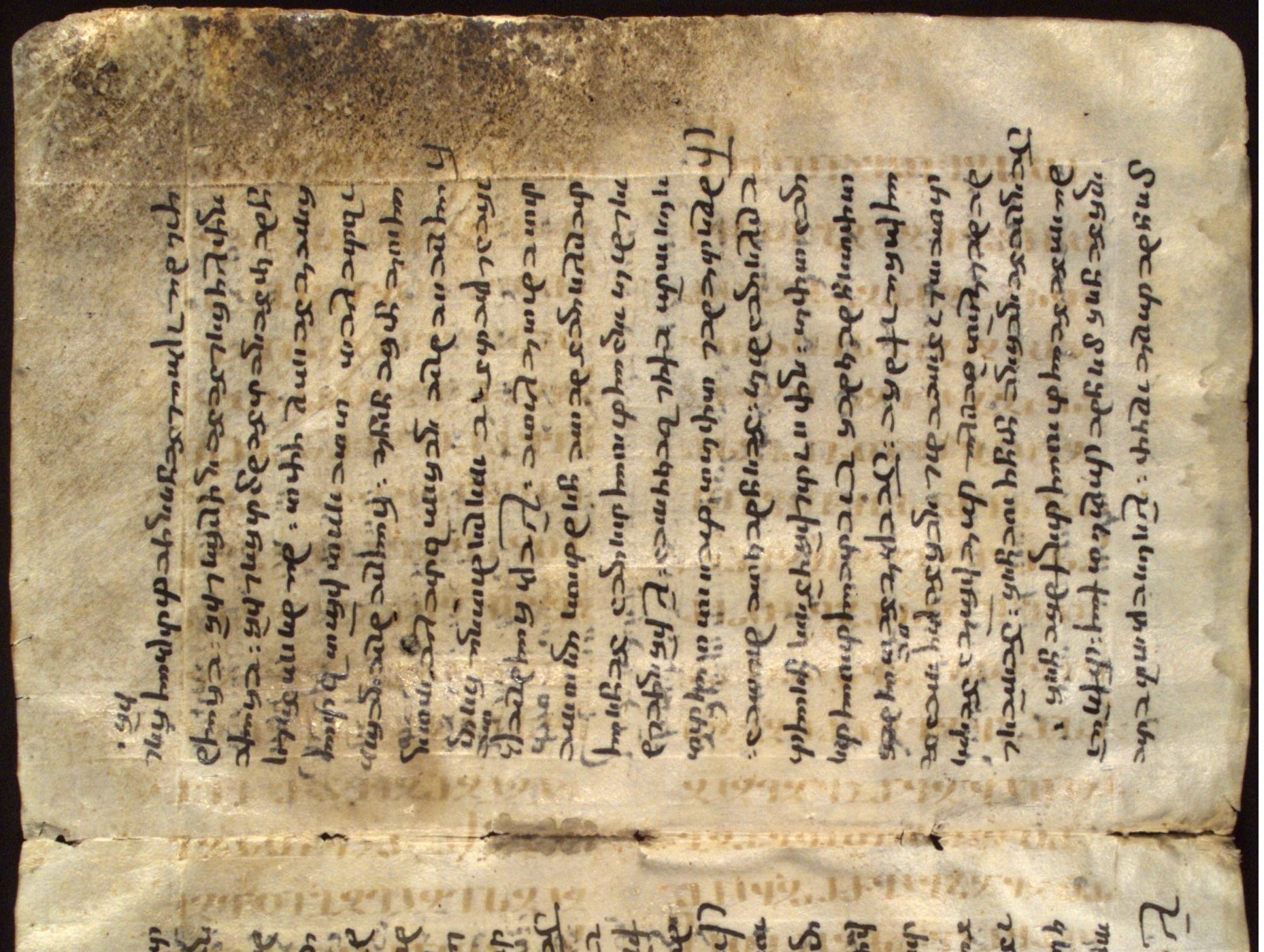

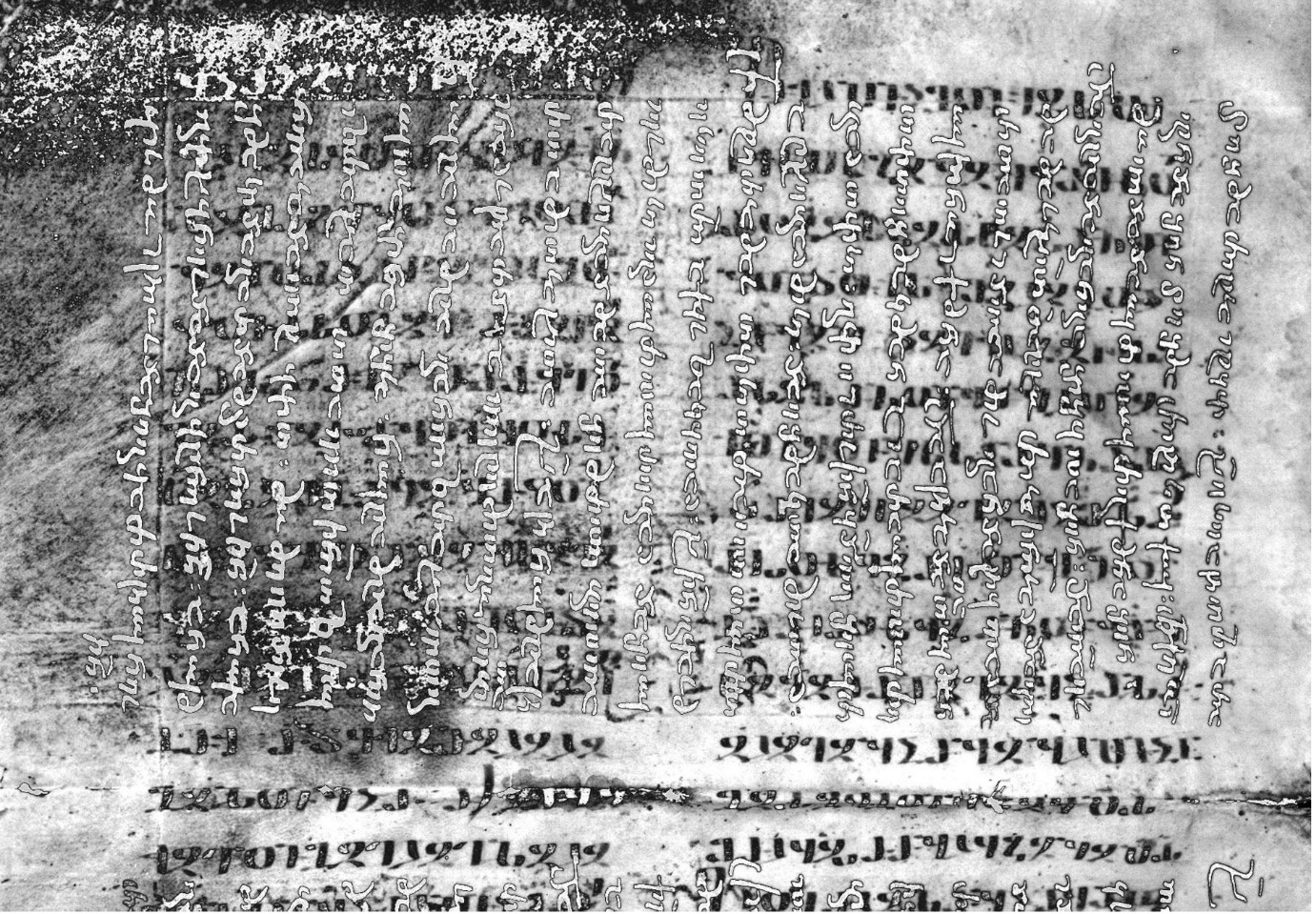

In the palimpsests with their biblical content (see Figures 1-2 showing passages from the 1st Letter of John and the Letter of James in the undertext of Sin. georg. NF 13, 4v), the Albanian language presents itself as strongly influenced not only by the neighbouring Christian traditions but also by other factors. The shape of biblical names proves that the Albanian Bible, at least the Gospel of John, was grounded on a Semitic, i.e. Syriac, tradition. This is clearly indicated by name forms like that of the lake Siloah (John 9.7 and 11) which appears as šiloha- in the palimpsests, thus matching Syriac šilōhāʾ and contrasting with Armenian siłovam and Georgian siloam- which both reflect Greek Σιλωάμ. Similarly, the name of the Samaritans appears as šamra- (John 4.9, 39-40; 8.48) matching Syriac šāmrā- and contrasting with Armenian samaracʽi and Georgian samariṭel-, which both again show the s- of Greek Σαμαρίτης [Gippert/Schulze 2023, 108 and 217-218]. The name of Moses appears in different forms in the Gospel of John and the other biblical texts of the palimpsests, which stem from a lectionary: in the former, it is mowše- (John 1.17; 5.45; 7.22) matching Syriac mowšeʾ while the latter have mowsēs (Matthew 17.3; Acts 13.38; Hebrews 3.2, 5; 11.24) in agreement with Armenian movsēs, Georgian mose- and Greek Μωϋσῆς, thus suggesting that the two palimpsested Albanian manuscripts represent different strata of the Bible translation in the language. However, “Syriacisms” are also found in the lectionary part as in the case of the name of the Sadducees which appears as zadoḳa- in Matthew 22.23, with its z- matching Syriac zadūqā- and opposing itself to s- in Armenian sadowkecʽi and Georgian saduḳevel- which reflect Greek Σαδδουκαῖος [Gippert/Schulze 2023, 140-141].

In its vocabulary, the Albanian language reveals influences from both Armenian and Georgian, especially in the core of Christian terminology [Gippert/Schulze 2023, 219-220]. So we find Georgian aġvseba- ‘Easter’ in Albanian axsiba-/axc̣iba- ‘id.’ (continued in modern Udi as axsibay/axc̣ima), madl-i ‘mercy, grace’ in Albanian madil’ ‘id.’, savrʒel-i ‘seat, see’ in Albanian sabowrzel ‘id.’, and saxē ‘face, appearance, vision’ in Albanian saxē ‘id.’. The word for ‘Friday’, Albanian ṗarasḳe (> Udi p/ṗarask/ḳi) matches Georgian ṗarasḳev-i, in its turn reflecting Greek παρασκευή, and Albanian angelos- ‘angel’, eḳlesi- ‘church’ and ḳeisar- ‘emperor’ < Greek ἄγγελος, ἐκκληςία and καῖσαρ are likely to have entered the language via Georgian angelos-, eḳ(ḳ)lesia-, and ḳeysar- (vs. Armenian hreštak, ekełecʽi, and kaysar). A true Armenian loan word is Albanian marmin’ ‘body, flesh’ while hetanos- ‘heathen, Gentile’ and salmos- ‘psalm’ are Greek words (ἔθνος, ψαλμός) in a peculiar Armenian disguise (hetʽanos, sałmos). An Armenian loan must also be the word for ‘congregation, synagogue’ which always appears abbreviated as ž˜d- in the Albanian palimpsests; the abbreviation obviously reflects Armenian zhoghovurd. A large bulk of the Albanian lexicon consists of Iranianisms, i.e. borrowings from Middle Iranian languages that were prevalent in the region in Antiquity; some but not all of them are matched by corresponding borrowings in Armenian and/or Georgian such as žam‑ ‘hour, time’ ~ Armenian zham, Georgian žam- < Middle Iranian *žam ‘id.’ or asṗarez- ‘stadion’ ~ Armenian asparēs, Georgian asparez- < Middle Iranian *asparēs ‘turning point of horse (races)’. A peculiar Iranianism in Albanian is e.g. bamgen ‘blessed’ (< Middle Iranian *bāmgēn ‘splendid’), and marġaven- ‘prophet’ reflects an Iranian word for ‘bird-seer’ similar to Armenian margarē- ‘id.’ but with a different verbal formation included (*marγa-wēn- vs. *marγa-δē‑) [Gippert 2005; Gippert/Schulze 2023, 215-217].

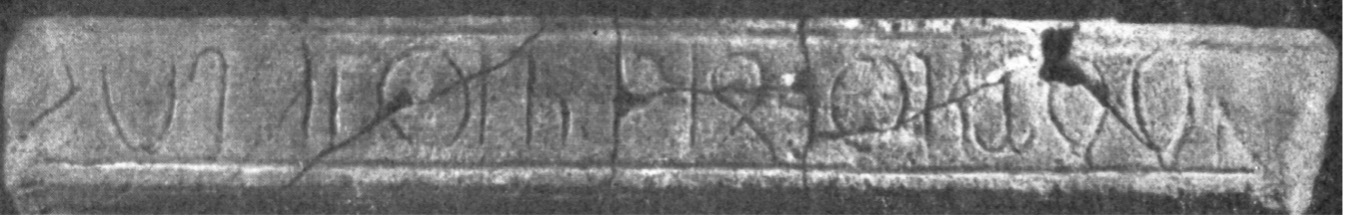

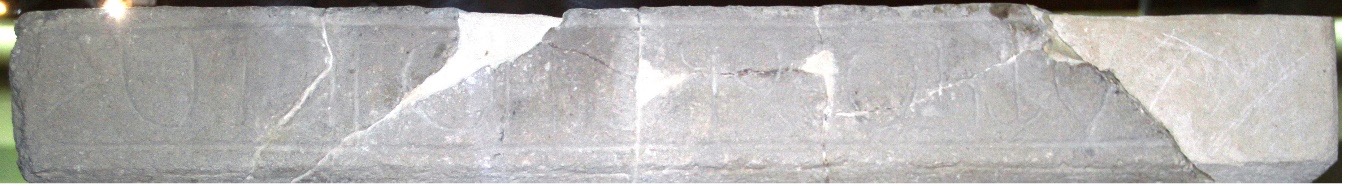

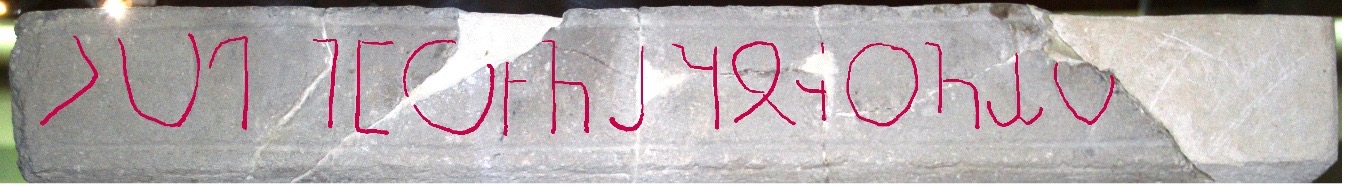

The decipherment of the palimpsests also facilitated the reading of the seven genuine Albanian inscriptions that have been unearthed so far (all in Mingachevir) [Gippert et al. 2008, II-85-94; Gippert 2023, 142-148]. Only one of them is of both linguistic and historical interest, namely, a four-part text line preserved on what is likely to have been the pedestal of a cross. Even though it is badly damaged, it clearly provides the name of a Sasanian emperor in whose 27th reignal year the cross was erected. With the name form xosroow- (see Figures 3-5) it may refer to either one of the two emperors named Khosrow (I Anushirvan, r. 531-579, and II Parviz, r. 590-628), thus yielding the years 557 and 616 as possible dates of the commemorated event. Even though for neither the inscriptions nor the palimpsested manuscripts any more precise dating is available, it is thus probable that the Albanian language ceased to be written shortly after the end of the Sasanian dominion in the Caucasus, along with the termination of the autocephaly of the Albanian church during the Arab rule in about the 8th century.

Bibliography

Abuladze, I. (Илья Абуладзе), “К открытию алфавита кавказских албанцев” [On the Detection of the Alphabet of the Caucasian Albanians], Bulletin de l’Institut Marr de Langues, d’Histoire et de Culture Matérielle / Известия Института Языка, Истории и Материальной Культуры им. Акад. Н. Я. Марра 4/1 (1938), p. 69-71. https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/handle/1234/317424.

Aleksidze, Z. – Mahé, J.-P., “Découverte d’un texte albanien : une langue ancienne du Caucase retrouvée”, Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 141 (1997), p. 517-532. https://www.persee.fr/doc/crai_0065-0536_1997_num_141_2_15756.

Bais, M., Albania Caucasica. Ethnos, storia, territorio attraverso le fonti greche, latine e armene, Milan: Mimesis 2001.

Bais, M., “Caucasian Albania in Greek and Latin Sources”, in J. Gippert – J. Dum-Tragut (eds), Caucasian Albania – An International Handbook, Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter 2023, p. 3-31. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110794687-001.

Brosset, M. F., “Extrait du manuscrit arménien no 114 de la Bibliothèque royale, relatif au calendrier géorgien”, Journal Asiatique 21 (= 2 e sér. 10) (1832), p. 526-532. https://www.retronews.fr/journal/journal-asiatique/01-dec-1832/339/1998201/46; https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb10248826.

Dum-Tragut, J. – Gippert, J., “Caucasian Albania in Medieval Armenian Sources (5th –13th Centuries)”, in J. Gippert – J. Dum-Tragut (eds), Caucasian Albania – An International Handbook, Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter 2023, p. 33-92. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110794687-002.

Gippert, J. 2005. “Armeno-Albanica”, in G. Schweiger (ed.), Indogermanica. Festschrift Gert Klingenschmitt, Taimering: Schweiger VWT-Verlag 2005, p. 155-165. https://www.academia.edu/21815861.

Gippert, J., “The Textual Heritage of Caucasian Albanian”, in J. Gippert, J. Dum-Tragut (eds), Caucasian Albania – An International Handbook, Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter 2023, p. 95-166. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110794687-003.

Gippert, J. – Schulze, W., “The Language of the Caucasian Albanians”, in J. Gippert, J. Dum-Tragut (eds), Caucasian Albania – An International Handbook, Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter 2023, p. 167-229. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110794687-004.

Gippert, J. –Schulze, W. – Aleksidze, Z. – Mahé, J.-P., The Caucasian Albanian Palimpsests of Mt. Sinai, vol. 1 (Monumenta Palaeographica Medii Aevi. Series Ibero-Caucasica 1), Turnhout: Brepols 2008.

Qaziyev, S. (Салеһ Мустафа оглы Казиев), “Новые археологические находки в Мингечауре” [New Archaeological Finds in Mingachevir], Азәрбаиҹан ССР Елмләр Академијасынын мә’рузәләри / Доклады Академии Наук Азербайджанской ССР [Reports of the Academy of Sciences of the Azerbaijanian SSR] IV/9 (1948), p. 396-403

Shanidze, A. (Акакий Шанидзе), “Новооткрытый алфавит кавказских албанцев и его значение для науки” [The Newly Discovered Alphabet of the Caucasian Albanians and Its Significance for Science], Bulletin de l’Institut Marr de Langues, d’Histoire et de Culture Matérielle / Известия Института Языка, Истории и Материальной Культуры им. Акад. Н. Я. Марра 4 (1938), p. 1-68. https://dspace.nplg.gov.ge/handle/1234/317424.

Vahidov, R. – Fomenko, V. P. (Рагим Меджит оглы Ваидов – В. П. Фоменко), “Средневековый храм в Мингечауре” [A Medieval Church in Mingechaur], Материальная культура Азербайджана [Material Culture of Azerbaijan] 2 (1951), p. 80-102.