Dadivankʻ Monastery (late 12th – 13th centuries)

Patrick Donabédian (Aix-Marseille University)

The monastery of St Dad (Dadi, Dadē) or Dadivankʻ, also called Khutʻavankʻ, is located on a flat area overlooking the left bank of the Těrtu/Tʻartʻaṛ/Terter river. It is named after a legendary disciple of the apostle Thaddeus, who was supposed to have come to evangelise Artsʻakh as early as the first century AD, and to have been martyred and buried on the site of the monastery. The date of the actual foundation of Dadivankʻ is unknown. It was destroyed by the Seljuk Turks in 1145-1146 and rebuilt from the end of the 12th century onwards, with most of its buildings dating from the 13th century. It was then an episcopal seat and the religious centre of the principality of Upper Khachʻēn. The complex was the subject of a major excavation and restoration campaign from 1997 to 2011.

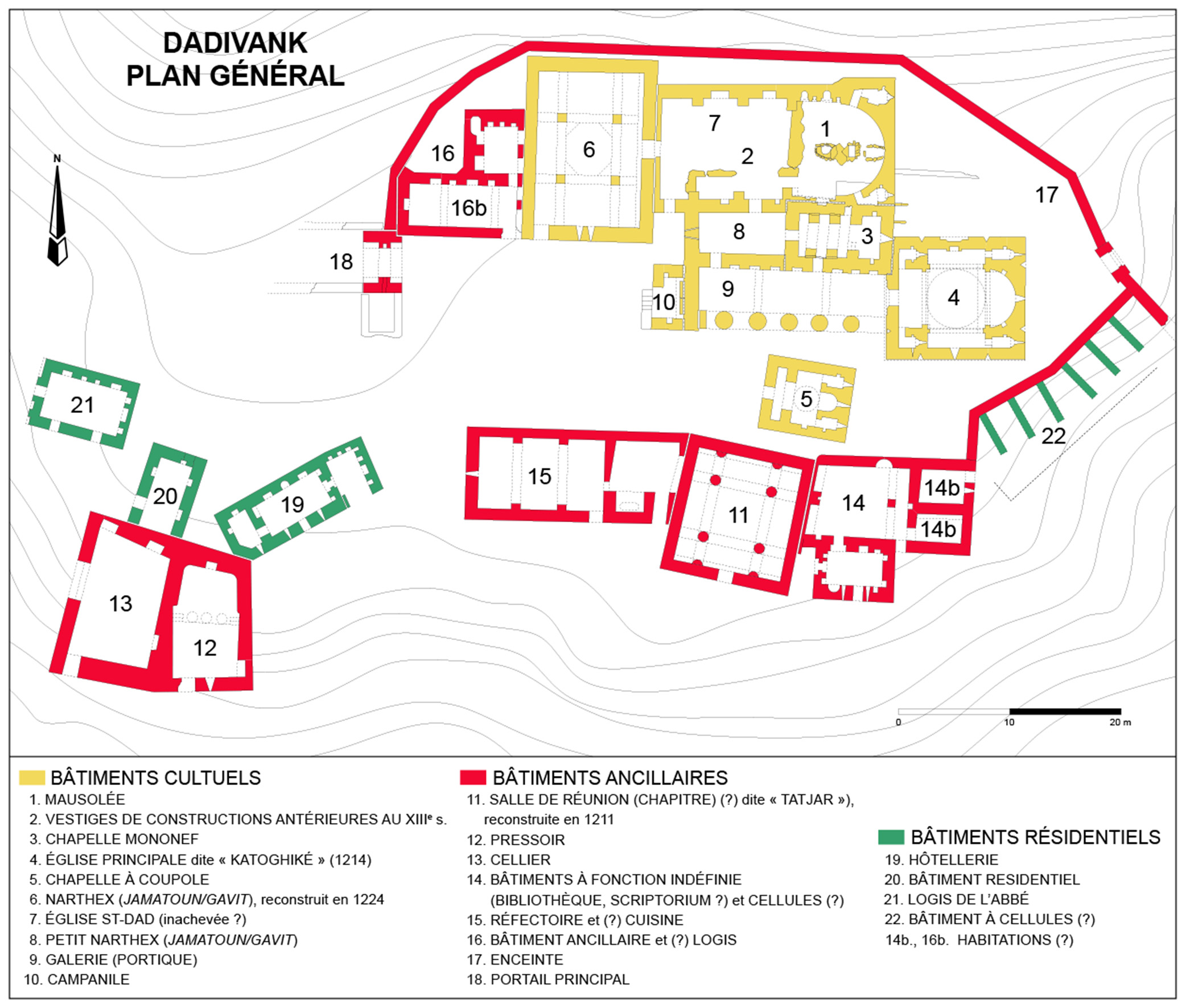

Dadivankʻ is one of the largest conventual complexes in medieval Armenia. Its twenty or so preserved buildings give a fairly complete picture of the organisation of an Armenian monastery (Fig. 1). Three functional groups correspond to the main spheres of monastic life: a) the worship group to the north, with two churches, two chapels, two narthexes, a campanile and a gallery; b) the group of monastic activities to the south (refectory, kitchen, chapter house, library and scriptorium [presumed functions]); c) the residential group to the south-west (with, in particular, a two-storey hostelry), completed with an oil press and a cellar.

In the northern part of the worship group, a large and wide single-nave church, curiously, it seems, unfinished (or designed to be covered in wood?), includes, in its eastern part, a funerary and memorial area comprising a pit, a stela and a tomb. These could be part of the (early Christian?) remains of the martyrium of St Dad. At a short distance to the south-east, the main church, katʻoghikē, although modest in plan, is the dominant building of the complex (Fig. 2, 3). The long inscription engraved on its southern façade indicates that it was built in 1214 by Princess Arzukhatʻun in memory of her husband Vakhtang and her sons Hasan and Grigor, who “died prematurely” (Fig. 4). The church has a dome on an inscribed cross and a compact plan. Its lower half has rather squat proportions, counterbalanced by the height of the large 14-sided drum with a pyramidal dome.

The church is the only one to be clad in carefully hewn blocks and is enlivened, especially at the level of the drum, by the contrast between its brick-coloured masonry and the blind colonnade-arcade carved in white stone. At the top of the south and east façades, two pairs of figures are sculpted in low relief on either side of the church model. They may represent the saintly dedicatee of the monastery and Prince Vakhtang on the east side; and the latter’s sons on the south side. The princes, who died before the construction, are haloed, but unlike the saint, whose head is entirely surrounded by a large nimbus, each of them is depicted with a small disc behind his head. They wear a high headdress typical of high-ranking nobles during the Georgian period. While the two princes on the south façade are shown full-height, wearing a long cloak tight around the waist, on the east façade the figures are shown in bust form; but it is possible that these sculptures have been deprived of their lower parts as a result of reworking. The bust of the saint, whose image is simplified, may have been sculpted anew on this occasion. Inside, two painted compositions partially cover the side walls: the Enthronement of St Nicholas on the south wall, and the Stoning of St Stephen on the north wall (Fig.4). These paintings, dated by inscription to 1297 and restored in 2014-15 by Christine Lamoureux and Ara Zarian, distinguish themselves by their quality—-in particular, by the finesse of the design and the expressiveness of the faces. Accompanied by captions in Armenian, they attest the existence of a high-level local art school, along with the attachment of the princes and the monastic community to the Armenian tradition and language.

To the south of the worship group, a chapel with a dome over an inscribed cross, with rustic masonry and a tile roof, is isolated in the courtyard (Fig. 5). Its high, slightly tapered cone-shaped drum is built mainly of brick. It is undated, but houses a khachʻkʻar whose inscription states that it was erected in 1182 by Prince Hasan, son of Vakhtang—-who became a monk and a member of the brotherhood. The narthex in front of the large single-nave church was built, as an inscription indicates, in 1224 by the superior Grigoris III. Much wider than it is long, it is of a type most common in Armenia at the time: four pillars support the dome with a central skylight, but it is distinguished by the slightly ogee shape of its arches. At the western end of the gallery that extends in front of the door of the main church stands a campanile whose modest appearance enhanced the splendour of the two khachʻkʻars that it housed until recently (Fig. 6). Sculptures of exceptional refinement and virtuosity, dated to 1283, they are among the most beautiful khachʻkʻars to be found in Armenia. After the cession of the territory to Azerbaijan in 2020, for fear of destruction or amputation, these two masterpieces were transferred to Ējmiatsin.

Further south, in the centre of the second group, a large hall with a square plan is referred to as a tachar (= palace, hall, temple) in its construction inscription of 1211. It is believed that it was actually founded slightly earlier and then remodelled, and that it corresponded to a chapter house. It has the same structure as the large narthex, with a truncated dome reposing on four columns. Its orientation is the same as that of the domed chapel, slightly deviated to the south-east if compared with the other buildings, which may indicate that the two buildings were erected at the same time, at a relatively early date, towards the end of the 12th century.

Bibliography

Ayvazyan, S. / Այվազյան, Ս., Դադի վանքի վերականգնումը 1997–2011 թթ. [The restoration of the monastery of Dad in 1997–2011], RAA 17, Yerevan: RAA, 2015.

Ayvazyan, S. – Sargsyan, G. / Այվազյան, Ս. – Սարգսյան, Գ., “Դադի վանքում 2008 թ. կատարված պեղումները” [The excavations carried out at the monastery of Dad in 2008], Վարձք 7 – Duty of Soul 7, Yerevan: RAA, 2012, p. 1–12.

Cuneo, P., Architettura armena, I, Rome: De Luca, 1988. On Dadivankʻ: p. 450-455.

Donabédian, P., “Main Monuments of Artsʻakh”, in I. Dorfmann-Lazarev – H. Khatchadourian (eds), Monuments and Identities in the Caucasus: Karabagh, Nakhichevan and Azerbaijan in Contemporary Geopolitical Conflict, Leiden – Boston: Brill, 2023, p. 102-172. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-04476628 On Dadivankʻ: p. 111-118.

Dum-Tragut, J., Maranci, Ch., La Porta, S., Armenian Cultural-Religious Heritage of Artsakh (Major Sites in the Territories Currently Occupied by Azerbaijan), Etchmiadzin: Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, 2021. On Dadivankʻ: p. 74-81.

Hasratʻyan, M. / Հասրաթյան, Մ., Հայկական ճարտարապետության Արցախի դպրոցը [The Artsʻakh School of Armenian Architecture], Yerevan: Academy of Sciences of Armenia, 1992. On Dadivankʻ: p. 43-61.

Karapetyan, S., Armenian Cultural Monuments in the Region of Karabakh, RAA 3, Yerevan: RAA, 2001. On Dadivankʻ: p. 74-121.

Karapetyan, S. / Կարապետյան, Ս., Մռավականք [The Mṛav Mountains Region], Հայաստանի պատմություն, հատոր Դ [History of Armenia, Volume IV], Yerevan: RAA, 2019. On Dadivankʻ: p. 291-355.

Lala Comneno, M.A., Cuneo, P., Manoukian, S., Gharabagh (Documenti di Architettura Armena 19), Milan: OEMME, 1988. On Dadivankʻ: p. 74-75, 102-103.

Matevosyan, K., Avetisyan, A., Zarian, A., Lamoureux, Ch., Dadivankʽ. Revived Miracle (in Armenian, Russian and English), Yerevan: “Victoria” Foundation, 2018.

Mkrtchʽyan, Sh. / Մկրտչյան, Շ., Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի պատմաճարտարապետական հուշարձանները [The historical-architectural monuments of Nagornȳĭ Karabakh], Yerevan: Hayastan, 1985. On Dadivankʻ: p. 38-46.

Mkrtchʽyan, Sh. / Мкртчян, Ш., Историко-архитектурные памятники Нагорного Карабаха [The historical-architectural monuments of Nagornȳĭ Karabakh], Yerevan: Hayastan, 1988. On Dadivankʻ: p. 34-39.

Sarkissian, St., Armenian Monuments and Remains in Artsakh / Monuments et vestiges arméniens en Artsakh, Yerevan: Collage, 2019. On Dadivankʻ: p. 104-105.

Thierry, J.-M., Églises et couvents du Karabagh, Antelias (Lebanon): Catholicossat arménien de Cilicie, 1991. On Dadivankʻ: p. 65-80.

Thierry, J.M. – Donabédian, P., Les arts arméniens, Paris: Mazenod,

- On Dadivankʽ: p. 511–512.

Zarian, A. – Lamoureux, Ch., Dadivank. La conservation-restauration des peintures murales datées de 1297 dans l’église Kathoghiké construite en 1214 (in Armenian and French), Yerevan: Tigran Mets, 2021.