Hasan Jalal, a great Armenian prince under the Mongols

Claude Mutafian (PhD History)

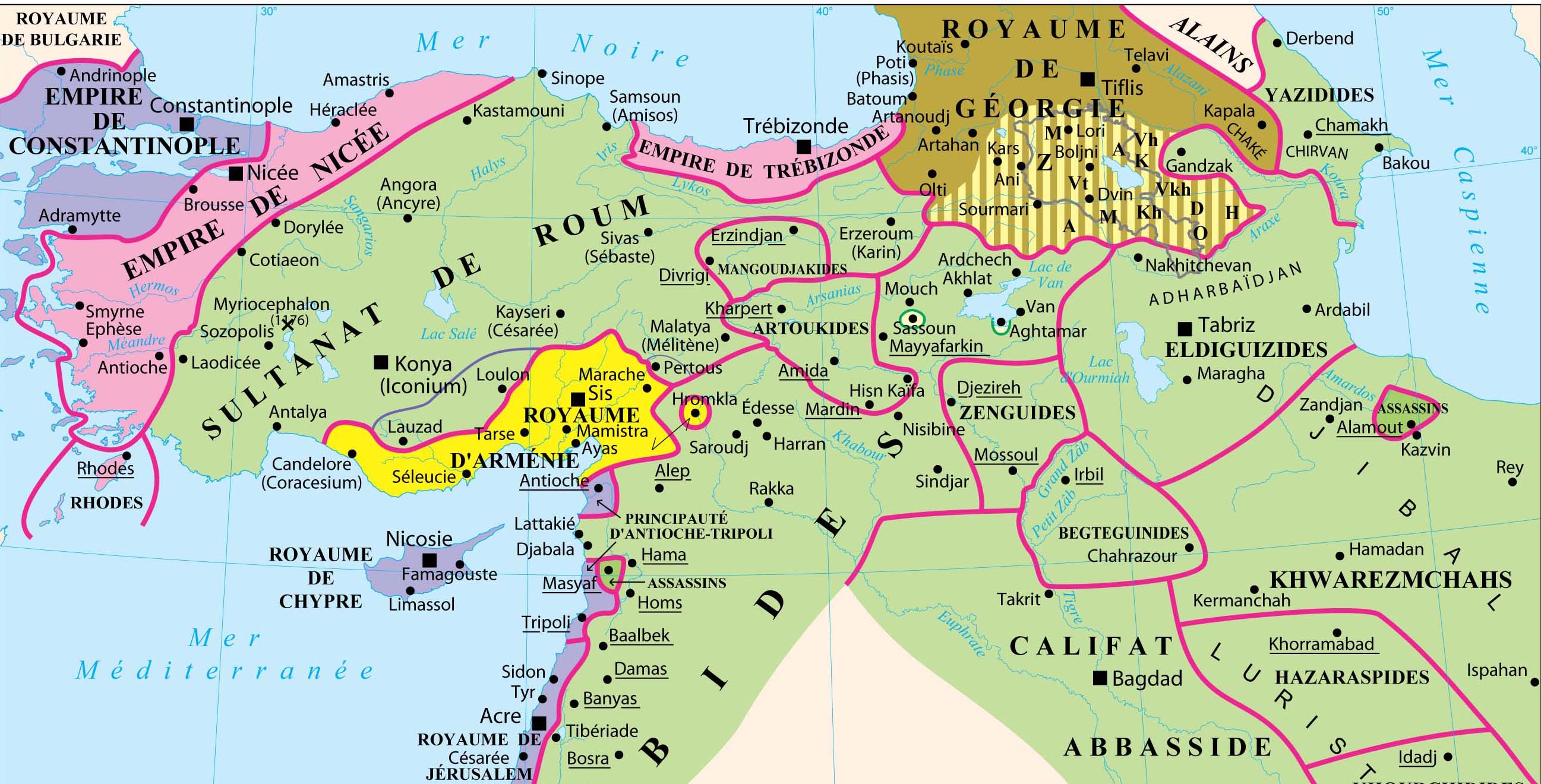

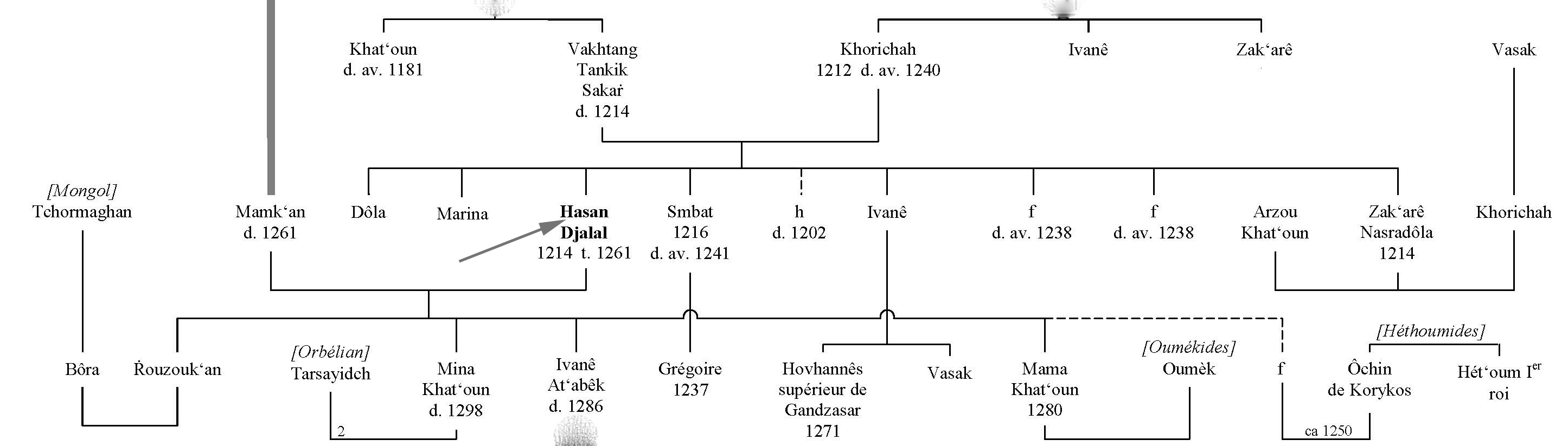

At the beginning of the 13th century, the kingdom of Armenia, which was located in Cilicia, was under threat from the powerful Turkish sultanate of Asia Minor (Fig. 1). In 1220, the Mongols arrived from Central Asia, invaded the Caucasus in 1236 and ravaged historic Armenia (KG XXII, p. 239; Baratov 1998, p. 114). Since 1214, Artsakh, a province of eastern Armenia, had been in the hands of an Armenian prince with Arabic nicknames – Hasan (handsome) Jalal (grandiose) Dawla (wealth), a great prince, a pious and honest man, an Armenian (KG LV, p. 358; Achaṛyan 1946, p. 56/41) – , nephew of the Zakarid princes Ivanē and Zakarē, whose date of birth is unknown (Fig. 2). He resisted their attacks to such an extent that the Mongols offered him the chance to go to them and seal an alliance, which took the form of the marriage of his daughter to the son of the Mongol general Ch’ormaghan. The deal paid off and temporarily lifted the Turkish threat, although it did not prevent the local tax collectors from committing atrocities. It was through Hasan Jalal that the Armenian king Het’um I decided to play his Mongol alliance policy against the Turks.

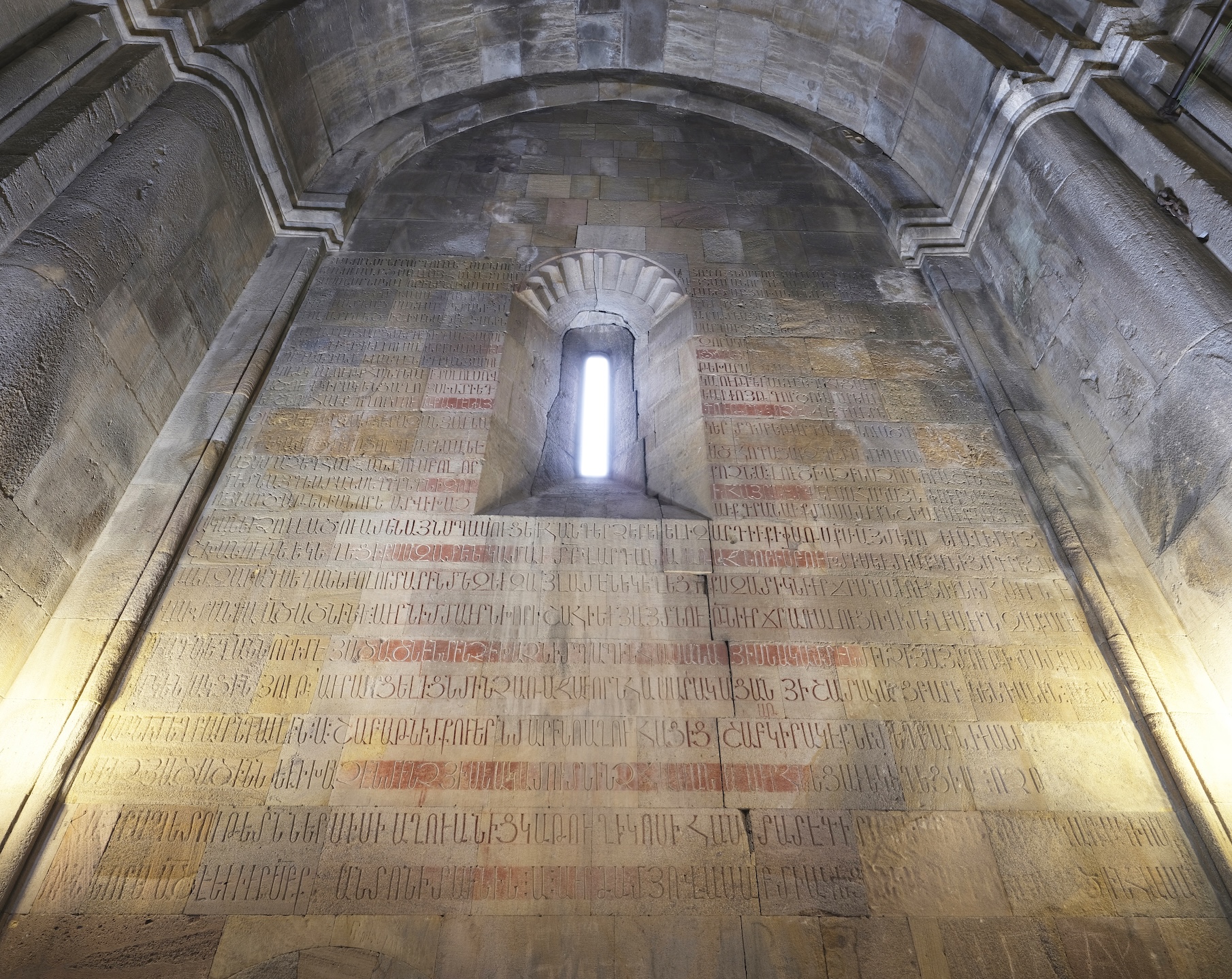

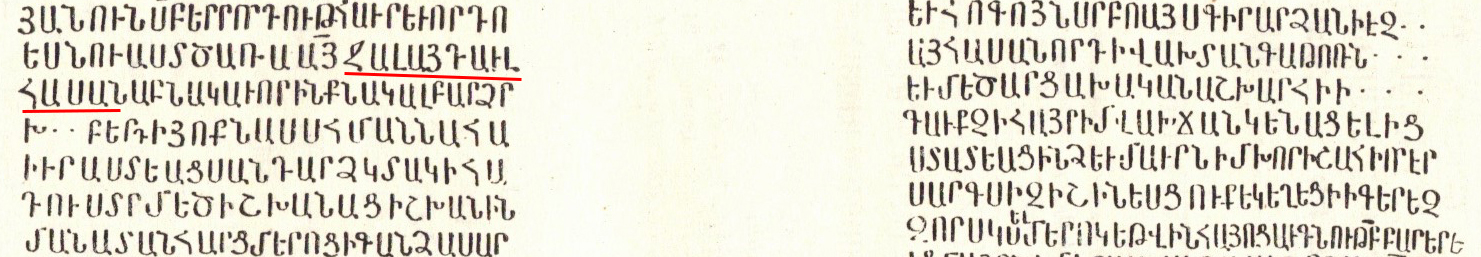

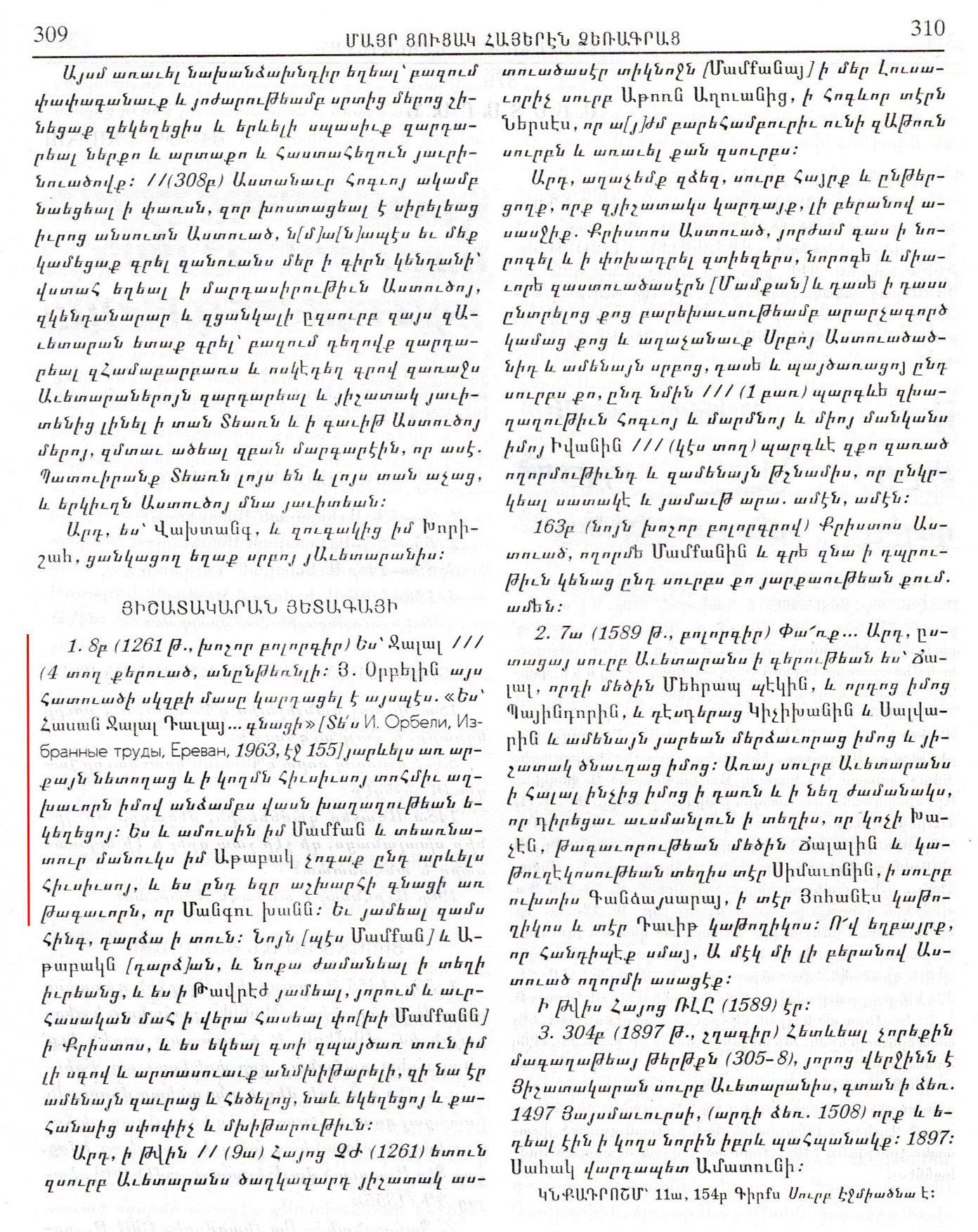

At the beginning of the long inscription engraved on the inner wall of the Gandzasar monastery (>> Gandzasar) (Fig. 3), which he built between 1216 and 1238, and which was consecrated in 1240, Hasan is described as “the legitimate autocrat of the great and high country of Artsakh” (DHV 82, p. 38; Mutafian 2022, p. 246) (Fig. 4–5). At the end he gives details of his family, in particular the names of his father “Vakhtang”, his mother “Khorishah”, who went to Jerusalem “where she lived for many years after her husband’s death”, and his wife “Mamk’an” (DHV 84, p. 41; Mutafian 2012, p. 316), princess of Siunik according to another inscription. He is explicitly known to have seven brothers and sisters. Faced with the Mongol campaigns, he initially tried to resist, but ended up submitting, like other Armenian lords who were thus able “to deliver, openly or secretly, many prisoners” (KG XXXV, p. 284). While the Mongol rulers were kind to their Christian subjects, the local tax collectors were particularly ruthless. Hasan made two trips to the East. In 1251, he visited Batu Khan of the Golden Horde, who confirmed his possession of his domains. In 1255, faced with the abuses of the local authorities, he undertook a second journey, documented in the colophon of an Evangeliary copied in Gandzasar in the 13th century (MS Mat. 378: Eganyan et al. 2004, col. 308-309; KG LV, p. 359) on commission from his parents (fol. 308; Fig. 6), where “Jalal” states (fol. 8v): “I went to the end of the world to King Mangu Khan and returned home after five years” (Fig. 7) . He then went to Tabriz, where he learned of the death of his father.

Things took a turn for the worse when, in 1260, the Mongol army suffered its first defeat in Syria, followed by the advent of the fearsome Mamluk sultan Baybars. At that time, the Christians of the Caucasus were burdened with taxes imposed by the Mongol administration. The historian Kirakos Gandzakets’i recounts in detail (KG LXIII, p. 390-391) the flight of the King of Georgia the following year and the reprisals of the Muslim prefect Arghun – for Islam was in vogue among the Mongols at the time. He arrested the family of the King of Georgia as well as Hasan Jalal, who tried in vain to bring Hulagu, Mongka’s brother and Mongol lord of Persia, directly to justice. Arghun reacted by subjecting him to appalling torture before putting him to death in 1260/61: “Thus died (...) this pure and pious man, who had ended his life by keeping his faith”. His son managed to recover his remains, which had been thrown into a well, and buried him in Gandzasar.

Hasan Jalal also remains, followed by his descendants, as a great builder, even outside Artsakh, and numerous inscriptions cover the walls of his monuments.

Bibliography

Hrach’ia Achaṛyan, Հայոց անձնանունների բառարան [Dictionnary of Armenian Proper Names], vol. 3, Yerevan, State University Press, 1946.

Boris Baratov, Paradise Laid waste: A Journey to Karabakh [translated from the Russian], Moscow: Lingvist, 1998.

DHV = Դիվան Հայ Վիմագրության [Corpus of Armenian Epigraphy], ed. Sedrak Barkhudaryan, vol. 5: Arts’akh, Yerevan : Academy of Sciences of Armenia, 1982.

KG = Kirakos Gandzakets’i, [History of Armenia], ed. Karapet Melik’-Ōhanjanyan, Yerevan : Matenadaran, 1961.

Ōnnik Eganean et al., Մայր Ցուցակ հայերէն ձեռագրաց Մաշտոցի անուան Մատենադարանի [Grand catalogue of the Armenian manuscripts of the Maštoc’ Matenadaran], vol. 2, Yerevan: Nairi 2004.

Claude Mutafian, L’Arménie du Levant, vol. 1, Paris : Les Belles Lettres, 2012.

Claude Mutafian, Jérusalem et les Arméniens, Paris : Les Belles Lettres, 2022.