Gandzasar Monastery (13th century)

Patrick Donabédian (Aix-Marseille University)

Mentioned in the 10th and 12th centuries as the episcopal seat of the principality of Khachʻēn, the monastery was built mainly in the 13th century. From the 14th to the beginning of the 19th century, Gandzasar was the seat of the “Catholicos of Caucasian Albania”, a title which had lost its ethnic connotation and which possessed a regional meaning. Several restorations are attested from the 16th century to the present day. From the end of the 17th, the Gandzasar catholicoi were at the forefront of the movement of liberation of Armenia from Persian and Ottoman domination.

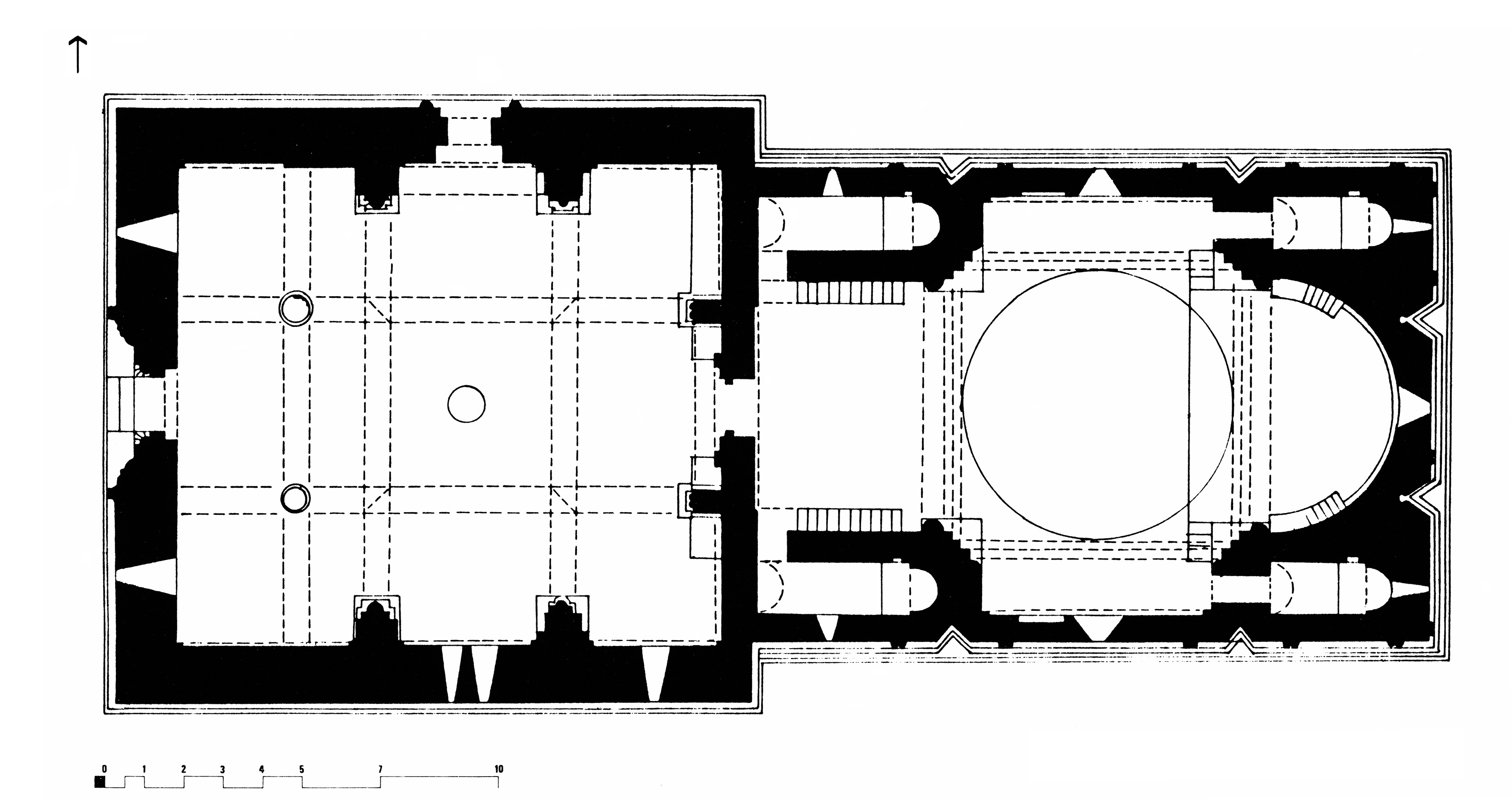

Gandzasar is a classic example of the core of medieval Armenian monasteries: the combination of the main church and the narthex attached to its western façade (Fig. 1). The unusually long construction period of these two edifices (almost fifty years in total) reflects the complexity of the conditions created by the unrest that preceded the Mongol invasion, the invasion itself and the subsequent occupation. Indeed, the inscriptions attest that the church of St John the Baptist was built between 1216 and 1238 by Prince Hasan Jalal-Dawla (an Armenian prince, despite his Arab-Persian names), and consecrated in 1240, and that the narthex (zhamatun) was founded by Hasan, his wife and their son Atʻabak, and completed by the latter in 1261 (or 1266), after the death of his father in 1260 or 1261.

These long works resulted in an exceptional quality of the edifices. The church is a construction with a dome over a partitioned, inscribed cross. It reproduces a composition very common in medieval Armenian monasteries: the four supports of the cupola are indivisible from the masonry of the four angular sacristy-chapels, each with two floors. The church is clad with very regularly cut blocks. Its elegant silhouette is strongly animated by the pairs of dihedral niches, the fine blind colonnade-arcade of the façades and, above all, by the high and wide sixteen-sided drum, punctuated by sixteen clusters of half-columns and topped by an umbrella-like dome which magnifies the verticality of the lines of the whole (Fig. 2). A brilliant creation of Armenian medieval architecture, the umbrella finds here one of its most outstanding manifestations.

The carved decoration is unusually abundant and of great diversity and quality—both in human and animal figures and in the elaborate plant and geometric ornamentation. The human figures are concentrated on the drum and on the west gable. On the latter is carved one of the rare Armenian monumental representations of Christ on the cross (Fig. 3). The treatment, however, is sufficiently hieratic and stylized, so that the image may not directly be associated with the human sufferings of Jesus Christ whom Armenian iconography generally prefers to show in his divine glory. There are numerous portraits of donors, certainly members of the Hasan-Jalalian dynasty. On the west gable, two of them are kneeling on either side of Christ, wearing the headgear of the Georgian nobility. One is struck by the clearly almond-shaped eyes of Christ, the angels and the princes, a sign perhaps of the choice of the latter to swear allegiance to the Mongols. On the south side of the drum, princesses and princes—who were probably deceased at the time of construction—wear a nimbus. On the western side of the drum, two bearded and moustached donors—presumably Hasan and his father Vakhtang—are depicted in a pose unexpected in this context: they are seated cross-legged, carrying a model of a church as an offering on a tray held above their heads (Fig. 4). One can distinguish a church with a dome on an inscribed cross on the right and a rotunda with an umbrella dome on the left. Inside the church, the four heads of the ‘living creatures’ (or symbols of the evangelists) are carved in the centre of the upper edge of the pendentives, at the foot of the drum. Their small size is compensated by their rather strong projection.

The façades are enriched by an arcade whose enlarged central portion is surmounted by a high cross (Fig. 2). This solution, of Georgian inspiration, as are the hanging festoons above the squinches that crown the two eastern dihedral niches, was common at the time in Armenia. The drum, in addition to the human figures already mentioned, has a very rich vegetal and geometric ornamentation inspired by that of the drum of Haṛich (1201), the first great Armenian sanctuary of the post-Seljuk period (Fig. 2, 3). Inside the church, the sculpted ornamentation, also prominent, adopts models then current in Armenia, common to both the Armenian and Muslim repertoires: arabesques and very elaborate interlacing, stalactites, broken sticks, etc. (Fig. 5). It adorns in particular the face of the elevation of the apse, the lower face of the steps of the corbelled staircases, the upper roll of the four central arches, the base belt of the drum and its cylindrical inner wall.

The narthex (zhamatun, or gawitʻ) is, as usual, a little wider and lower than the church in front of which it is built (Fig. 1, 2). The high thickness of its walls ensures full absorption of the thrusts of the heavy vault. This type of building is mainly used in Armenian monasteries as a burial place for members of the clergy and the local princely dynasty. This is confirmed in Gandzasar by the numerous tombstones and their inscriptions. The building has a sophisticated type of covering, present in numerous Armenian narthexes of the 13th century: its vault is supported by two pairs of crossed arches that rest on supports leaning against the peripheral walls (Fig. 6); on the west side, however, these arches are supported by a pair of free columns, which allows for an extension of the building towards the west (Fig. 1). In this respect, the narthex of Gandzasar is similar to those of Haghbat and Mshkavankʻ (13th century, Republic of Armenia). Inside, the vault that rises above the central square is carved with stalactites (muqarnas), of impeccable craftsmanship, also common at the time in Armenia, as well as on Seljuk monuments in Asia Minor. The four-sloped roof of the zhamatun and the hexastyle lantern above it were rebuilt in 1907.

On the outside, the zhamatun is distinguished by the considerable size of the western portal and its rich decoration (Fig. 7). Occupying almost the entire height of the façade, the composition uses original formulas: inlaid intersecting circles on the tympanum, an intermediate frame surrounding the door and the window, the rather marked relief of two large peacocks on either side of the window and a third large frame consisting of a wide torus whose decoration is original. This curved band is decorated with alternating oval and rectangular cartouches with very elaborate floral motifs, the treatment of which is unusual for a stone sculpture. The motifs emerge not by hollowing out the surface around them, but by digging out their inner void spaces, a technique more reminiscent of chiselling on metal or wood than of stone bas-relief. This powerful curved band continues horizontally, without ornamentation, at the bottom of the walls of the building, completing the series of steps that underline and strengthen the base of this imposing construction.

Bibliography

Cuneo, P., Architettura armena, I, Rome: De Luca, 1988. On Gandzasar: p. 443-445.

Donabédian, P., “Main Monuments of Artsʻakh”, in I. Dorfmann-Lazarev – H. Khatchadourian (eds), Monuments and Identities in the Caucasus: Karabagh, Nakhichevan and Azerbaijan in Contemporary Geopolitical Conflict, Leiden – Boston: Brill, 2023, p. 102-172. On Gandzasar: p. 153-161.

Hasratʻyan, M. / Հասրաթյան, Մ., Հայկական ճարտարապետության Արցախի դպրոցը [The Artsʽakh School of Armenian Architecture], Yerevan: Academy of Sciences of Armenia, 1992. On Gandzasar: p. 31-43.

Lala Comneno, M.A., Cuneo, P., Manoukian, S., Gharabagh (Documenti di Architettura Armena 19), Milan: OEMME, 1988. On Gandzasar: p. 76-79, 104-105.

Mkrtchʻyan, A. / Մկրտչյան, Ա., Գանձասար [Gandzasar], Yerevan: Tigran Mets, 2010.

Mkrtchʻyan, Sh. / Մկրտչյան, Շ., Լեռնային Ղարաբաղի պատմաճարտարապետական հուշարձանները [The historical-architectural monuments of Nagornȳĭ Karabakh], Yerevan: Hayastan, 1985. On Gandzasar: p. 9-15.

Mkrtchʻyan, Sh. / Мкртчян, Ш., Историко-архитектурные памятники Нагорного Карабаха [The historical-architectural monuments of Nagornȳĭ Karabakh], Yerevan: Hayastan, 1988. On Gandzasar: p. 14-19.

Sarkissian, St., Armenian Monuments and Remains in Artsakh / Monuments et vestiges arméniens en Artsakh, Yerevan: Collage, 2019. On Gandzasar: p. 102-103.

Thierry, J.-M., Églises et couvents du Karabagh, Antelias (Lebanon): Catholicossat arménien de Cilicie, 1991. On Gandzasar: p. 119-129.

Thierry, J.M. – Donabédian, P., Les arts arméniens, Paris: Mazenod,

- On Gandzasar: p. 526.

Ulubabian, B. – Hasratian, M., Gandzasar (Documenti di Architettura Armena 17), Milan: OEMME, 1987.

Ulubabyan, B. / Ուլուբաբյան, Բ., Գանձասար [Gandzasar], Yerevan: Hayastan, 1981.