The writing centers and manuscript heritage of Artsakh

Tamar Minasyan (Senior Researcher, Matenadaran, Yerevan)

Artsakh, the tenth province of Greater Armenia, is one of the oldest settlements of the Armenian written culture, and the local writing centers (calligraphy centers) are ranked among the Armenian medieval schools. In those centers, talented scribes and illustrators (miniature painters) have copied various theological, doctrinal, translational, historical, scientific, interpretive, educational and ritual manuscripts. The latter testify to the path and development of the Armenian written culture in those regions over the centuries. The records of manuscripts created in Artsakh are extremely important sources that provide remarkable information about the history of the province, its spiritual life, writing centers, patriarchs, scholarly priests, talented scribes and illustrators, clients and donors. The illuminated manuscripts with their art of illustration and stylistic features testify to the unique school of miniature painting and its high level of development.

The first center of writing of Artsakh was the Monastery of Amaras (Fig. 1), from which unfortunately no handwritten manuscripts have reached us. The writing centers of Gandzasar, Dadivank‘, Khadavank‘ (Khatravank‘), Gtch‘avank‘, the Monastery of St. Hakob of Metsaranats‘, Yerits‘ Mankants‘ Monastery, Yeghishē Arak‘ial (Apostle) Monastery, Avetaranots‘, Kusanats‘ Anapat, Gandzak and K‘arahat were notable, where talented scribes and illustrators worked. In the 17th century, female scribes were also known in Artsakh: the nuns Gayanē (Fig. 2), Katarinē and Varvaṛē (Fig. 3), whose manuscripts have survived to us.

The centers of writing had their own Manuscript Libraries (Matenadaran) with rich collections of manuscripts. Worthy of attention is the Armenian lithographic inscription of 1204 (the inscription of Hat‘erk‘) brought from Khadavank‘ and exhibited in the Matenadaran of Yerevan, which is the earliest written evidence of the creation of medieval Manuscript Libraries and museums in Artsakh (Fig. 4).

The oldest dated manuscript that has come down to us from Artsakh is the Datastanagirk‘ (Book of Judgments) by Mkhit‘ar Gosh written in 1184. Mkhit‘ar Gosh began writing it in Dasno Anapat [Dasno Desert], finished it in Hat‘erk‘, and dedicated it as a special gift to the Prince of Hat‘erk‘, Vakhtang and his wife, Arzukhatun. The manuscript is Gosh’s autograph. It is now kept in the library of the Mekhitarist Congregation of Venice (Venice, MS 993).

The rise of cultural life and especially the creation of writing centers and their active activity gradually contributed to the development of miniature art. As early as the 13th century, there were beautifully illustrated manuscripts, which are currently considered valuable examples of Artsakh’s writing art and Armenian manuscript culture. The miniatures of that period are notable for the unique iconography of church altars, title pages, and unique solutions of nationally characteristic ornaments. Artsakh miniaturists used simpler forms in their miniatures, and in their coloring they harmonized four or five colors: red, green, blue, purple and yellow.

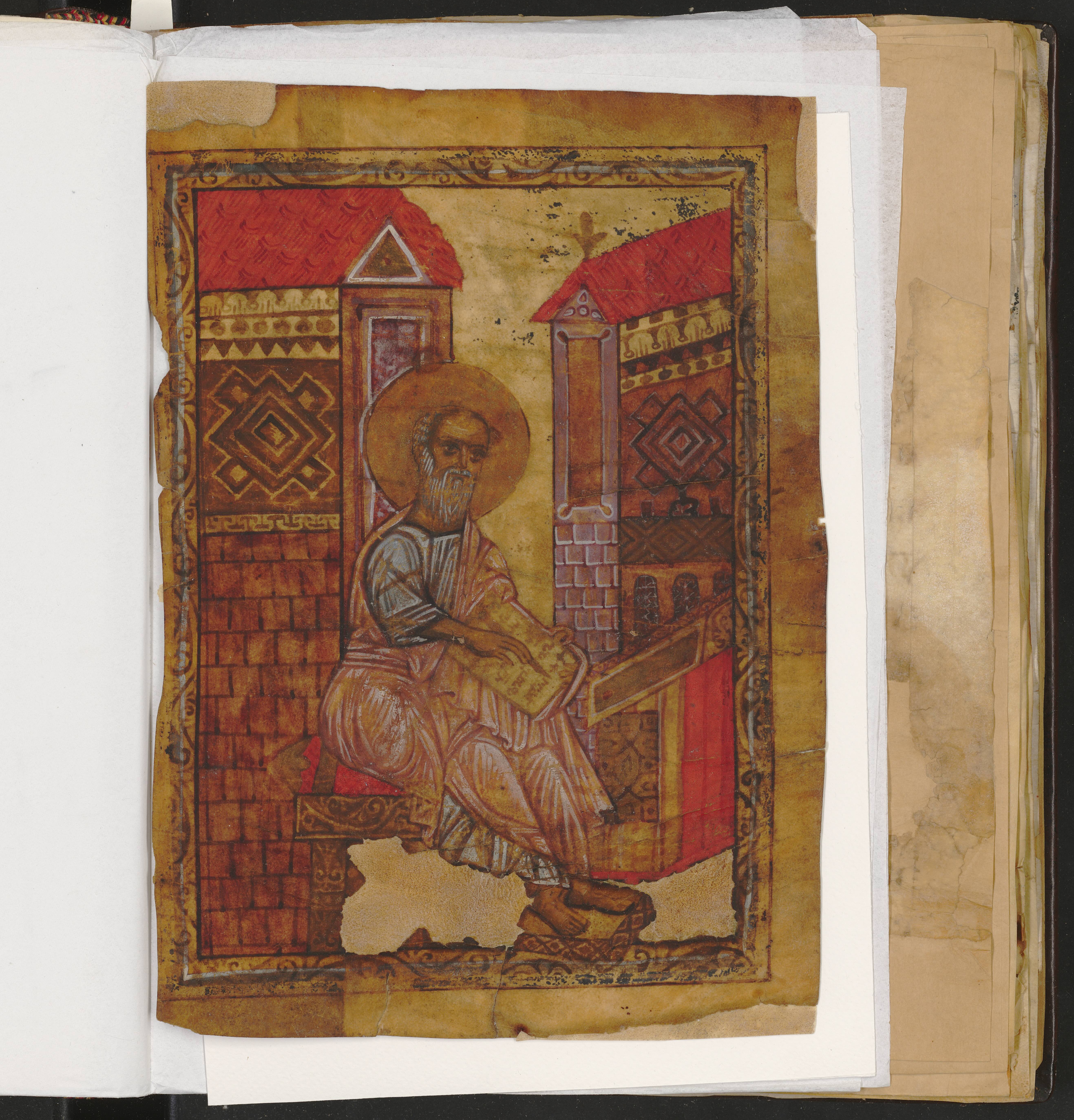

One of the notable manuscripts is the parchment Gospel (in erkat‘agir “uncial”) copied by the scribe T‘oros in 1212–1214 by order of Vakhtang-Tangik and Khorisah, the parents of the Prince of Artsakh, Hasan Jalal-Dola. The latter is the oldest illustrated manuscript created in Gandzasar and has survived to us (Gospel of Vakhtang-Tangik, Matenadaran MS 378). The manuscript contains ten altars, portraits of the evangelists, title pages and beautiful margin decorations (Fig. 5). The miniaturist painted the episode of the Ascension in the square of the title page of the Gospel of John (Fig. 6). There is also one image of the Lord in the Gospel, i.e. the Virgin Mary with the Child (Fig. 7).

Among the miniature paintings of Artsakh, the portrait of Vakhtang, son of Umek (Matenadaran, MS 155) is notable for its originality. In the 13th century, an unknown miniaturist painted a young prince sitting on a beautifully decorated high chair (Fig. 8). The young prince’s personality was emphasized in his delicate features and princely clothing. The character of Vakhtang reflected the lifestyle of a medieval Armenian nobleman, which had exceptional ethnographic significance.

The parchment Gospel called T‘argmanch‘ats‘ Avetaran (Matenadaran, MS 2743) written by the scribe of the Tirats‘i in 1232 and created by Grigor Tsaghkogh is exceptionally valuable. The place of writing is unknown. Grigor Tsaghkogh (Grigor the Illustrator) along with the scribe illustrated church altars, title pages, margin decorations and letters of the manuscript (Fig. 9–10). The portraits of the evangelists of the Gospel and the series of images of the Lord were painted in Khadavank‘ in the 14th century by the miniaturist Grigor of Artsakh.

Illustrated manuscripts of the late 13th and 14th centuries of Artsakh contain images of church altars, portraits of the evangelists, title pages and several images of the Lord (called Terunakan). The thematic paintings of the manuscripts have unique iconographic solutions, which often differ from the forms adopted in other schools of Armenian miniature painting.

Among the miniatures of Artsakh, the Terunakans of a Gospel copied in the 14th century (Matenadaran, MS 316) are interesting. In the depiction of the Annunciation (Avetum) of the manuscript, the archangel announces the good news to Mary by playing the flute (Fig. 11). This form is new in the miniature art. The iconographic form of the Last Supper (Khorhrdawor ǝnt‘rik‘) is also modern. In this painting, Jesus Christ and the eleven apostles are sitting around a circular table in the Upper Room (Vernatun) with halos on their heads, and Judas is separated from the general group in the lower right corner (Fig. 12). Both of these forms of iconography are found for the first time in Artsakh miniature painting.

The art of writing in Artsakh continued its normal activity in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries. A new outline was taking shape in the art of 17th-century Artsakh manuscripts. In parallel with traditional miniature painting, the miniaturists of Artsakh introduced features of the iconographic system that were characteristic of Cilician art. In the 17th century, the school of K‘arahat was famous (Fig. 13–14).

In parallel with the copying of manuscripts, bookbinding workshops also operated in the writing centers, where the art of bookbinding was developed as a branch of decorative applied art (Fig. 15-19). Artsakh craftsmen have created leather covers for manuscripts as well as silver and gilded double covers, each of which is the best example of art and amazes with its artistic decoration and variety of ornamental motifs.

Due to its unassailable location and long-term preservation, Artsakh is also known as a place of rescued and preserved manuscripts. In the monasteries and churches, villages and houses of individuals of Artsakh, exceptionally valuable manuscript books written in the various writing centers of Armenia and Cilicia and brought to Artsakh through donations or redemption were also kept. Each of these manuscripts is a separate masterpiece. Memoirs testify that when the princes of Artsakh returned from wars or travels, they also saved and brought Armenian manuscripts with them.

Among the manuscripts kept in various places of Artsakh, the following are notable: the oldest complete Armenian manuscript, the Vehamor Avetaran (Gospel, Matenadaran, MS 10680, 7th century), the Vehapari Avetaran (Gospel, Matenadaran, MS 10780, 10th century, Fig. 20), the Gospel (Matenadaran, MS 6202, year 909) copied in Constantinople by the scribe Tutael by order of the Commander Ashot, nephew of the Armenian King Smbat I (850–914), the Gospel of Haghbat‘ (Matenadaran, MS 6288, year 1211, fig. 21), the Gospel copied by the scribe Step‘anos by order of Queen Keran (Matenadaran, MS 6764, year 1283, fig. 22), the Begyunts‘ Avetaran (Gospel, Matenadaran, MS 10099, 10th–11th centuries, fig. 23) illustrated by Yovhannēs Sandghkavanets‘i and kept in the village of Talish, from which relics remained, the Red Gospel of Chicago (Chicago, MS 949, 13th century), the Gospel of Karin [or Theodopolis] (Venice, MS 129, year 1230), and others.

Of the thousands of manuscripts written, illustrated and preserved in Artsakh, we have information about 460 manuscripts, of which the whereabouts of 150 are unknown. Most of the manuscripts that have come down to us are kept in the Matenadaran of Yerevan, while others are in various manuscript libraries and private collections around the world.